Climbing the Social Ladder

Clay Shirky spoke at Harvard Law School two years ago and proudly proclaimed, “Group action just got easier.” He discusses a “ladder” of group interactions that begin with sharing. On the first rung of the ladder, someone begins sharing media online, sometimes for a specific purpose and other times just for fun. This shared artifact implicitly attracts people from diversely remote locations, often times strangers, and brings them together around a particular media piece (text, picture, music, video, etc.). At this point, the media content suddenly transforms into what cartoonist and entrepreneur, Hugh Macleod, calls a “social object”. According to Macleod, “The Social Object, in a nutshell, is the reason two people are talking to each other, as opposed to talking to somebody else.” He goes on to state that, “Social Networks form around Social Objects, not the other way around.”

Once the shared social object has a motivated social network surrounding it, people may then use their common interest in the object to discover related common interests, objectives, and goals. Ultimately this can encourage temporary collaborations that remain active until the mutual objective or goal is reached. At the top of the ladder is collective action. According to Shirky, collective action requires the highest level of individual commitments. Shirky believes that simply publishing media in the first place often reveals a desire or motivation for action. The interesting part, however, is how publishing initiates a social process in which the media attracts, inspires, catalyzes, and engages other like-minded individuals so that they may become sufficiently motivated to join the call for action. The most difficult factor will likely be maintaining enough sustained motivation and commitment to complete the collective task at hand and fully achieve the common goals of the ad-hoc group before the group naturally dissolves.

Once the shared social object has a motivated social network surrounding it, people may then use their common interest in the object to discover related common interests, objectives, and goals. Ultimately this can encourage temporary collaborations that remain active until the mutual objective or goal is reached. At the top of the ladder is collective action. According to Shirky, collective action requires the highest level of individual commitments. Shirky believes that simply publishing media in the first place often reveals a desire or motivation for action. The interesting part, however, is how publishing initiates a social process in which the media attracts, inspires, catalyzes, and engages other like-minded individuals so that they may become sufficiently motivated to join the call for action. The most difficult factor will likely be maintaining enough sustained motivation and commitment to complete the collective task at hand and fully achieve the common goals of the ad-hoc group before the group naturally dissolves.

Moo-ving into a Virtual Collaborative Space

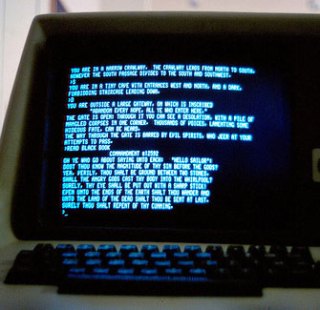

With all the hype and press surrounding the new opportunities that Web 2.0 provides for two-way-interaction and online collaboration, it’s easy to assume that virtual social objects and social networking are new concepts. However, researchers have been experimenting in this space since the dawn of the internet. For example, the MIT Media Lab introduced MediaMOO, 17 years ago, back in 1993. According to Amy Bruckman & Mitchel Resnick, MediaMOO is “a text-based, networked, virtual reality environment designed to enhance professional community among media researchers.” It was designed to allow researchers to extend relationships and collaborations that are initiated at physical conferences into their daily lives. It was based on the concept of MUDs or Multi-User Domains, in which users navigate a physical world via text commands. These environments initially became popular among Dungeons and Dragons players and other fantasy crowds, where the virtual worlds were designed for role-playing and interactive fiction. The first widely-used MUDs, Adventure – Colossal Caves and Zork, emerged in the 1970s. If you are curious, you can still explore these MUDs today:

It didn’t take long for others outside of the gaming world to realize the benefits of MUDs. Bruckman & Resnick used MediaMOO to test out the theory of constructivism within a virtual social space. The theory of constructivism is popular among teachers and often used when teaching children. It asserts that “people construct their own understanding and knowledge of the world, through experiencing things and reflecting on those experiences.” Basically this means that people learn better when they are active participants, partnering with the teacher to think critically, problem solve, and build artifacts. This is why shared activities in MediaMOO often included construction of even the virtual world itself. Bruckman & Resnick discovered that interactions among media researchers using the MUD were much more beneficial when users participated in a shared activity and everyone had the ability (and responsibility) to build the virtual world in the manner that they saw fit. Today, MUDs are big business as they have morphed into more visually sophisticated graphical MUDs such as World of Warcraft and Second Life. Many groups and businesses, including IBM recognize the potential value of such environments and have put significant resources toward setting up virtual space inside these worlds. Using Wikipedia as an example, Shirky illustrates just how powerful and successful the theory of constructivism can be when applied on a massive scale.

Let’s Build Something Together!

Will Richardson recognizes the same benefits that Bruckman & Resnick did with today’s “Read/Write Web”, his nickname for Web 2.0. He is encouraging educators to play the role of co-learners with their students as they actively work together to break through the traditional walls of the physical classroom. Richardson believes it is important that teachers help students expand their collaborations and learning activities into a more global virtual world through the medium of Read/Write Web tools such as blogs, forums, wikis, podcasts, etc. He sees classrooms as “media centers to the world.”

What I personally find interesting are all the potential media applications of constructivism and virtual social objects in politics and civic affairs. For example, Hervé Glevarec looked at youth radio in France as a “social object” in one of his studies. In this article, he shows “how radio is a medium particularly able to exploit its dual nature as both conversation and device, text and frame, conversational exchange and social interaction.” Glevarec inquires about what various radio programs represent for youth listeners within a social, interactive context. Clay Shirky, in his Harvard Law speech, discussed how one passenger who was stuck on an NWA airplane out on the tarmac for 7+ hours co-opted online media to canvass and assemble other frustrated passengers. These passengers collaborated to generate a non-partisan, populist petition that ultimately led to an airline “Passenger Bill of Rights” being signed by congress in 2007.

Time for Something a Little More Flashy

In truth, virtually any political issue may be turned into a social object that can then be used to recruit and network activists. Frank Luntz learned that by simply renaming something, such as the “Estate Tax”, using words that are more emotionally provocative, a person can generate mass interest in an issue and leverage that interest to get people to collaborate and/or take collective political action. Some feel that Luntz’s application was a rather deceitful and an unprincipled use of this strategy, but nevertheless, the results were quite revealing. These various case studies inspire me to explore how social networks might be generated by citizens to rapidly respond to government and corporate actions that are deemed unfavorable and undesirable by particular groups of constituents who are adversely affected.

Shirky, in his Harvard speech, also describes how kids in Eastern Europe used Bill Wasik’s satirical flash mob idea for real political purposes to help them expose and document their government’s oppressive actions. In the same vein, if random flash mobs can so easily be organized, why couldn’t symbolic “flash boycotts” and “flash protests” be organized in the wake of company policy announcements that consumers find to be unfair or inappropriate?

A More Perfect Union

Workers have often relied on collective organization and action through the use of unions. Historically, this was easier because they usually shared the same physical space (i.e. a factory or store). It was a straightforward task to recruit these workers since they all were employed within the same organization. However, until now, it has been much more difficult for widely dispersed and unrelated consumers to come together and “unionize” in order to challenge companies who have overstepped their boundaries. The citizens of Wells, Maine proved the effectiveness of such online collective action by using web media to stop Nestle from unfairly extracting water from their municipal ground sources.

This is the real power of the Read/Write Web. When social objects are used to harness the power of social networking, it can bring passionate and motivated individuals together to collaboratively learn and forge real relationships. Just like the researchers in MediaMOO, the gamers in Zork, or the students in Richardson’s future classrooms, frustrated citizens and consumers can now work together to actively construct virtual worlds that will ultimately lead to the construction of new, and hopefully better, physical worlds.